Shareholder letters archive

Annual Shareholder Letters from BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.

SHAREHOLDER LETTER 2009

Berkshire’s recent acquisition of Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) has added at least 65,000 shareholders to the 500,000 or so already on our books. It’s important to Charlie Munger, my long-time partner, and me that all of our owners understand Berkshire’s operations, goals, limitations and culture. In each annual report, consequently, we restate the economic principles that guide us. This year these principles appear on pages 89-94 and I urge all of you – but particularly our new shareholders – to read them. Berkshire has adhered to these principles for decades and will continue to do so long after I’m gone.

In this letter we will also review some of the basics of our business, hoping to provide both a freshman orientation session for our BNSF newcomers and a refresher course for Berkshire veterans.

HOW WE MEASURE OURSELVES

WHAT WE DON’T DO

Here are a few examples of how we apply Charlie’s thinking at Berkshire:

- Charlie and I avoid businesses whose futures we can’t evaluate, no matter how exciting their products may be. In the past, it required no brilliance for people to foresee the fabulous growth that awaited such industries as autos (in 1910), aircraft (in 1930) and television sets (in 1950). But the future then also included competitive dynamics that would decimate almost all of the companies entering those industries. Even the survivors tended to come away bleeding.Just because Charlie and I can clearly see dramatic growth ahead for an industry does not mean we can judge what its profit margins and returns on capital will be as a host of competitors battle for supremacy. At Berkshire we will stick with businesses whose profit picture for decades to come seems reasonably predictable. Even then, we will make plenty of mistakes.

- We will never become dependent on the kindness of strangers. Too-big-to-fail is not a fallback position at Berkshire. Instead, we will always arrange our affairs so that any requirements for cash we may conceivably have will be dwarfed by our own liquidity. Moreover, that liquidity will be constantly refreshed by a gusher of earnings from our many and diverse businesses.When the financial system went into cardiac arrest in September 2008, Berkshire was a supplier of liquidity and capital to the system, not a supplicant. At the very peak of the crisis, we poured $15.5 billion into a business world that could otherwise look only to the federal government for help. Of that, $9 billion went to bolster capital at three highly-regarded and previously-secure American businesses that needed – without delay – our tangible vote of confidence. The remaining $6.5 billion satisfied our commitment to help fund the purchase of Wrigley, a deal that was completed without pause while, elsewhere, panic reigned.We pay a steep price to maintain our premier financial strength. The $20 billion-plus of cashequivalent assets that we customarily hold is earning a pittance at present. But we sleep well.

- We make no attempt to woo Wall Street. Investors who buy and sell based upon media or analyst commentary are not for us. Instead we want partners who join us at Berkshire because they wish to make a long-term investment in a business they themselves understand and because it’s one that follows policies with which they concur. If Charlie and I were to go into a small venture with a few partners, we would seek individuals in sync with us, knowing that common goals and a shared destiny make for a happy business “marriage” between owners and managers. Scaling up to giant size doesn’t change that truth.To build a compatible shareholder population, we try to communicate with our owners directly and informatively. Our goal is to tell you what we would like to know if our positions were reversed. Additionally, we try to post our quarterly and annual financial information on the Internet early on weekends, thereby giving you and other investors plenty of time during a non-trading period to digest just what has happened at our multi-faceted enterprise. (Occasionally, SEC deadlines force a non-Friday disclosure.) These matters simply can’t be adequately summarized in a few paragraphs, nor do they lend themselves to the kind of catchy headline that journalists sometimes seek.Last year we saw, in one instance, how sound-bite reporting can go wrong. Among the 12,830 words in the annual letter was this sentence: “We are certain, for example, that the economy will be in shambles throughout 2009 – and probably well beyond – but that conclusion does not tell us whether the market will rise or fall.” Many news organizations reported – indeed, blared – the first part of the sentence while making no mention whatsoever of its ending. I regard this as terrible journalism: Misinformed readers or viewers may well have thought that Charlie and I were forecasting bad things for the stock market, though we had not only in that sentence, but also elsewhere, made it clear we weren’t predicting the market at all. Any investors who were misled by the sensationalists paid a big price: The Dow closed the day of the letter at 7,063 and finished the year at 10,428.Given a few experiences we’ve had like that, you can understand why I prefer that our communications with you remain as direct and unabridged as possible.

- We tend to let our many subsidiaries operate on their own, without our supervising and monitoring them to any degree. That means we are sometimes late in spotting management problems and that both operating and capital decisions are occasionally made with which Charlie and I would have disagreed had we been consulted. Most of our managers, however, use the independence we grant them magnificently, rewarding our confidence by maintaining an owneroriented attitude that is invaluable and too seldom found in huge organizations. We would rather suffer the visible costs of a few bad decisions than incur the many invisible costs that come from decisions made too slowly – or not at all – because of a stifling bureaucracy.With our acquisition of BNSF, we now have about 257,000 employees and literally hundreds of different operating units. We hope to have many more of each. But we will never allow Berkshire to become some monolith that is overrun with committees, budget presentations and multiple layers of management. Instead, we plan to operate as a collection of separately-managed mediumsized and large businesses, most of whose decision-making occurs at the operating level. Charlie and I will limit ourselves to allocating capital, controlling enterprise risk, choosing managers and setting their compensation.

Let’s move to the specifics of Berkshire’s operations. We have four major operating sectors, each differing from the others in balance sheet and income account characteristics. Therefore, lumping them together, as is standard in financial statements, impedes analysis. So we’ll present them as four separate businesses, which is how Charlie and I view them.

Insurance

An old Wall Street joke gets close to our experience:

Here is the record of all four segments of our property-casualty and life insurance businesses:

GEICO’s managers, it should be emphasized, were never enthusiastic about my idea. They warned me that instead of getting the cream of GEICO’s customers we would get the – – – – – well, let’s call it the non-cream. I subtly indicated that I was older and wiser.

I was just older.

Regulated Utility Business

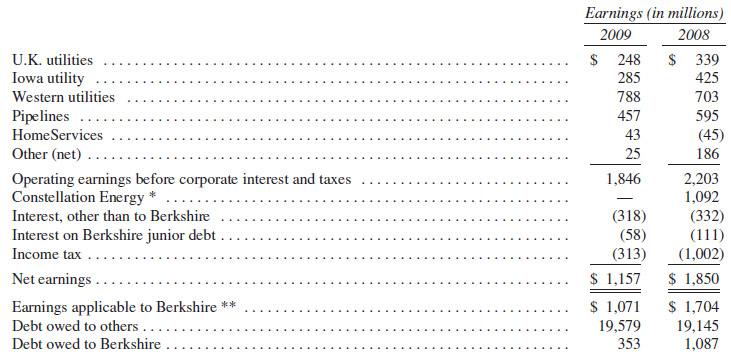

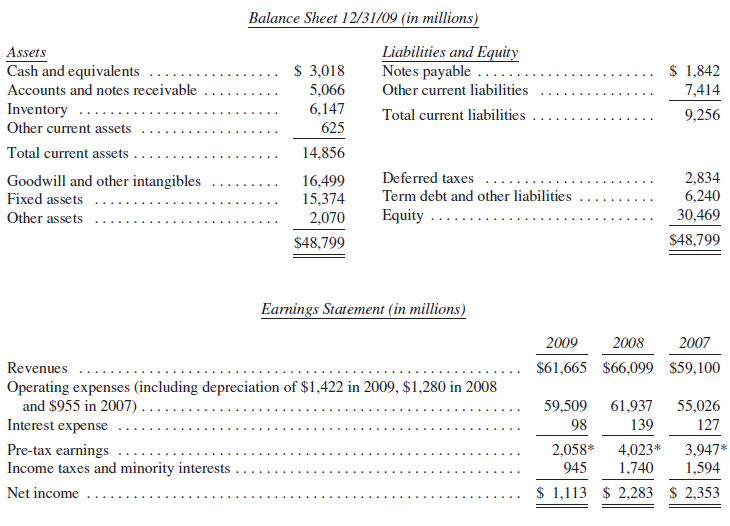

Here are some key figures on MidAmerican’s operations:

We had a number of companies at which profits improved even as sales contracted, always an exceptional managerial achievement. Here are the CEOs who made it happen:

Among the businesses we own that have major exposure to the depressed industrial sector, both Marmon and Iscar turned in relatively strong performances. Frank Ptak’s Marmon delivered a 13.5% pre-tax profit margin, a record high. Though the company’s sales were down 27%, Frank’s cost-conscious management mitigated the decline in earnings.

Most important, none of the changes wrought by Dave have in any way undercut the top-of-the-line standards for safety and service that Rich Santulli, NetJets’ previous CEO and the father of the fractionalownership industry, insisted upon. Dave and I have the strongest possible personal interest in maintaining these standards because we and our families use NetJets for almost all of our flying, as do many of our directors and managers. None of us are assigned special planes nor crews. We receive exactly the same treatment as any other owner, meaning we pay the same prices as everyone else does when we are using our personal contracts. In short, we eat our own cooking. In the aviation business, no other testimonial means more.

Finance and Financial Products

The industry is in shambles for two reasons, the first of which must be lived with if the U.S. economy is to recover. This reason concerns U.S. housing starts (including apartment units). In 2009, starts were 554,000, by far the lowest number in the 50 years for which we have data. Paradoxically, this is good news. People thought it was good news a few years back when housing starts – the supply side of the picture – were running about two million annually. But household formations – the demand side – only amounted to about 1.2 million. After a few years of such imbalances, the country unsurprisingly ended up with far too many houses.

There were three ways to cure this overhang: (1) blow up a lot of houses, a tactic similar to the destruction of autos that occurred with the “cash-for-clunkers” program; (2) speed up household formations by, say, encouraging teenagers to cohabitate, a program not likely to suffer from a lack of volunteers or; (3) reduce new housing starts to a number far below the rate of household formations.

Our country has wisely selected the third option, which means that within a year or so residential housing problems should largely be behind us, the exceptions being only high-value houses and those in certain localities where overbuilding was particularly egregious. Prices will remain far below “bubble” levels, of course, but for every seller (or lender) hurt by this there will be a buyer who benefits. Indeed, many families that couldn’t afford to buy an appropriate home a few years ago now find it well within their means because the bubble burst.

The second reason that manufactured housing is troubled is specific to the industry: the punitive differential in mortgage rates between factory-built homes and site-built homes. Before you read further, let me underscore the obvious: Berkshire has a dog in this fight, and you should therefore assess the commentary that follows with special care. That warning made, however, let me explain why the rate differential causes problems for both large numbers of lower-income Americans and Clayton.

The residential mortgage market is shaped by government rules that are expressed by FHA, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. Their lending standards are all-powerful because the mortgages they insure can typically be securitized and turned into what, in effect, is an obligation of the U.S. government. Currently buyers of conventional site-built homes who qualify for these guarantees can obtain a 30-year loan at about 51/4%. In addition, these are mortgages that have recently been purchased in massive amounts by the Federal Reserve, an action that also helped to keep rates at bargain-basement levels.

Last year I told you why our buyers – generally people with low incomes – performed so well as credit risks. Their attitude was all-important: They signed up to live in the home, not resell or refinance it. Consequently, our buyers usually took out loans with payments geared to their verified incomes (we weren’t making “liar’s loans”) and looked forward to the day they could burn their mortgage. If they lost their jobs, had health problems or got divorced, we could of course expect defaults. But they seldom walked away simply because house values had fallen. Even today, though job-loss troubles have grown, Clayton’s delinquencies and defaults remain reasonable and will not cause us significant problems.

We have tried to qualify more of our customers’ loans for treatment similar to those available on the site-built product. So far we have had only token success. Many families with modest incomes but responsible habits have therefore had to forego home ownership simply because the financing differential attached to the factory-built product makes monthly payments too expensive. If qualifications aren’t broadened, so as to open low-cost financing to all who meet down-payment and income standards, the manufactured-home industry seems destined to struggle and dwindle.

Even under these conditions, I believe Clayton will operate profitably in coming years, though well below its potential. We couldn’t have a better manager than CEO Kevin Clayton, who treats Berkshire’s interests as if they were his own. Our product is first-class, inexpensive and constantly being improved. Moreover, we will continue to use Berkshire’s credit to support Clayton’s mortgage program, convinced as we are of its soundness. Even so, Berkshire can’t borrow at a rate approaching that available to government agencies. This handicap will limit sales, hurting both Clayton and a multitude of worthy families who long for a low-cost home.

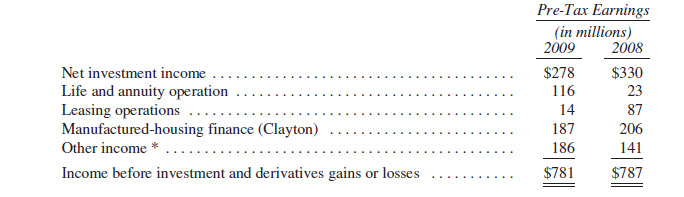

In the following table, Clayton’s earnings are net of the company’s payment to Berkshire for the use of its credit. Offsetting this cost to Clayton is an identical amount of income credited to Berkshire’s finance operation and included in “Other Income.” The cost and income amount was $116 million in 2009 and $92 million in 2008.

The table also illustrates how severely our furniture (CORT) and trailer (XTRA) leasing operations have been hit by the recession. Though their competitive positions remain as strong as ever, we have yet to see any bounce in these businesses.

At the end of 2009, we became a 50% owner of Berkadia Commercial Mortgage (formerly known as Capmark), the country’s third-largest servicer of commercial mortgages.

Investments

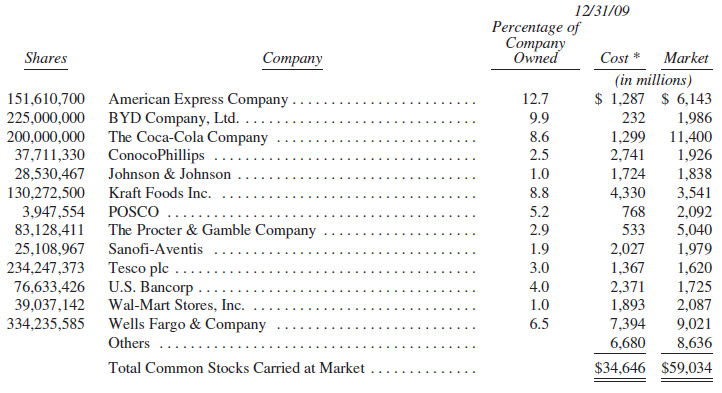

Below we show our common stock investments that at yearend had a market value of more than $1 billion.

In addition, we own positions in non-traded securities of Dow Chemical, General Electric, Goldman Sachs, Swiss Re and Wrigley with an aggregate cost of $21.1 billion and a carrying value of $26.0 billion. We purchased these five positions in the last 18 months. Setting aside the significant equity potential they provide us, these holdings deliver us an aggregate of $2.1 billion annually in dividends and interest. Finally, we owned 76,777,029 shares (22.5%) of BNSF at yearend, which we then carried at $85.78 per share, but which have subsequently been melded into our purchase of the entire company.

In 2009, our largest sales were in ConocoPhillips, Moody’s, Procter & Gamble and Johnson & Johnson (sales of the latter occurring after we had built our position earlier in the year). Charlie and I believe that all of these stocks will likely trade higher in the future. We made some sales early in 2009 to raise cash for our Dow and Swiss Re purchases and late in the year made other sales in anticipation of our BNSF purchase.

We told you last year that very unusual conditions then existed in the corporate and municipal bond markets and that these securities were ridiculously cheap relative to U.S. Treasuries. We backed this view with some purchases, but I should have done far more. Big opportunities come infrequently. When it’s raining gold, reach for a bucket, not a thimble.

Last year I wrote extensively about our derivatives contracts, which were then the subject of both controversy and misunderstanding. For that discussion, please go to www.berkshirehathaway.com.

We have since changed only a few of our positions. Some credit contracts have run off. The terms of about 10% of our equity put contracts have also changed: Maturities have been shortened and strike prices materially reduced. In these modifications, no money changed hands.

A few points from last year’s discussion are worth repeating:

(1) Though it’s no sure thing, I expect our contracts in aggregate to deliver us a profit over their lifetime, even when investment income on the huge amount of float they provide us is excluded in the calculation. Our derivatives float – which is not included in the $62 billion of insurance float I described earlier – was about $6.3 billion at yearend.

(2) Only a handful of our contracts require us to post collateral under any circumstances. At last year’s low point in the stock and credit markets, our posting requirement was $1.7 billion, a small fraction of the derivatives-related float we held. When we do post collateral, let me add, the securities we put up continue to earn money for our account.

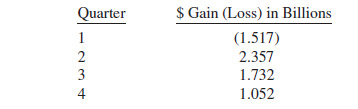

(3) Finally, you should expect large swings in the carrying value of these contracts, items that can affect our reported quarterly earnings in a huge way but that do not affect our cash or investment holdings. That thought certainly fit 2009’s circumstances. Here are the pre-tax quarterly gains and losses from derivatives valuations that were part of our reported earnings last year:

We have long invested in derivatives contracts that Charlie and I think are mispriced, just as we try to invest in mispriced stocks and bonds. Indeed, we first reported to you that we held such contracts in early 1998. The dangers that derivatives pose for both participants and society – dangers of which we’ve long warned, and that can be dynamite – arise when these contracts lead to leverage and/or counterparty risk that is extreme. At Berkshire nothing like that has occurred – nor will it.

It’s my job to keep Berkshire far away from such problems. Charlie and I believe that a CEO must not delegate risk control. It’s simply too important. At Berkshire, I both initiate and monitor every derivatives contract on our books, with the exception of operations-related contracts at a few of our subsidiaries, such as MidAmerican, and the minor runoff contracts at General Re. If Berkshire ever gets in trouble, it will be my fault. It will not be because of misjudgments made by a Risk Committee or Chief Risk Officer.

In my view a board of directors of a huge financial institution is derelict if it does not insist that its CEO bear full responsibility for risk control. If he’s incapable of handling that job, he should look for other employment. And if he fails at it – with the government thereupon required to step in with funds or guarantees – the financial consequences for him and his board should be severe.

It has not been shareholders who have botched the operations of some of our country’s largest financial institutions. Yet they have borne the burden, with 90% or more of the value of their holdings wiped out in most cases of failure. Collectively, they have lost more than $500 billion in just the four largest financial fiascos of the last two years. To say these owners have been “bailed-out” is to make a mockery of the term.

The CEOs and directors of the failed companies, however, have largely gone unscathed. Their fortunes may have been diminished by the disasters they oversaw, but they still live in grand style. It is the behavior of these CEOs and directors that needs to be changed: If their institutions and the country are harmed by their recklessness, they should pay a heavy price – one not reimbursable by the companies they’ve damaged nor by insurance. CEOs and, in many cases, directors have long benefitted from oversized financial carrots; some meaningful sticks now need to be part of their employment picture as well.

An Inconvenient Truth (Boardroom Overheating)

The reason for our distaste is simple. If we wouldn’t dream of selling Berkshire in its entirety at the current market price, why in the world should we “sell” a significant part of the company at that same inadequate price by issuing our stock in a merger?

In evaluating a stock-for-stock offer, shareholders of the target company quite understandably focus on the market price of the acquirer’s shares that are to be given them. But they also expect the transaction to deliver them the intrinsic value of their own shares – the ones they are giving up. If shares of a prospective acquirer are selling below their intrinsic value, it’s impossible for that buyer to make a sensible deal in an all-stock deal. You simply can’t exchange an undervalued stock for a fully-valued one without hurting your shareholders.

Imagine, if you will, Company A and Company B, of equal size and both with businesses intrinsically worth $100 per share. Both of their stocks, however, sell for $80 per share. The CEO of A, long on confidence and short on smarts, offers 11/4 shares of A for each share of B, correctly telling his directors that B is worth $100 per share. He will neglect to explain, though, that what he is giving will cost his shareholders $125 in intrinsic value. If the directors are mathematically challenged as well, and a deal is therefore completed, the shareholders of B will end up owning 55.6% of A & B’s combined assets and A’s shareholders will own 44.4%. Not everyone at A, it should be noted, is a loser from this nonsensical transaction. Its CEO now runs a company twice as large as his original domain, in a world where size tends to correlate with both prestige and compensation.

If an acquirer’s stock is overvalued, it’s a different story: Using it as a currency works to the acquirer’s advantage. That’s why bubbles in various areas of the stock market have invariably led to serial issuances of stock by sly promoters. Going by the market value of their stock, they can afford to overpay because they are, in effect, using counterfeit money. Periodically, many air-for-assets acquisitions have taken place, the late 1960s having been a particularly obscene period for such chicanery. Indeed, certain large companies were built in this way. (No one involved, of course, ever publicly acknowledges the reality of what is going on, though there is plenty of private snickering.)

In our BNSF acquisition, the selling shareholders quite properly evaluated our offer at $100 per share. The cost to us, however, was somewhat higher since 40% of the $100 was delivered in our shares, which Charlie and I believed to be worth more than their market value. Fortunately, we had long owned a substantial amount of BNSF stock that we purchased in the market for cash. All told, therefore, only about 30% of our cost overall was paid with Berkshire shares.

In the end, Charlie and I decided that the disadvantage of paying 30% of the price through stock was offset by the opportunity the acquisition gave us to deploy $22 billion of cash in a business we understood and liked for the long term. It has the additional virtue of being run by Matt Rose, whom we trust and admire. We also like the prospect of investing additional billions over the years at reasonable rates of return. But the final decision was a close one. If we had needed to use more stock to make the acquisition, it would in fact have made no sense. We would have then been giving up more than we were getting.

I have been in dozens of board meetings in which acquisitions have been deliberated, often with the directors being instructed by high-priced investment bankers (are there any other kind?). Invariably, the bankers give the board a detailed assessment of the value of the company being purchased, with emphasis on why it is worth far more than its market price. In more than fifty years of board memberships, however, never have I heard the investment bankers (or management!) discuss the true value of what is being given. When a deal involved the issuance of the acquirer’s stock, they simply used market value to measure the cost. They did this even though they would have argued that the acquirer’s stock price was woefully inadequate – absolutely no indicator of its real value – had a takeover bid for the acquirer instead been the subject up for discussion.

When stock is the currency being contemplated in an acquisition and when directors are hearing from an advisor, it appears to me that there is only one way to get a rational and balanced discussion. Directors should hire a second advisor to make the case against the proposed acquisition, with its fee contingent on the deal not going through. Absent this drastic remedy, our recommendation in respect to the use of advisors remains: “Don’t ask the barber whether you need a haircut.”

I can’t resist telling you a true story from long ago. We owned stock in a large well-run bank that for decades had been statutorily prevented from acquisitions. Eventually, the law was changed and our bank immediately began looking for possible purchases. Its managers – fine people and able bankers – not unexpectedly began to behave like teenage boys who had just discovered girls.

They soon focused on a much smaller bank, also well-run and having similar financial characteristics in such areas as return on equity, interest margin, loan quality, etc. Our bank sold at a modest price (that’s why we had bought into it), hovering near book value and possessing a very low price/earnings ratio. Alongside, though, the small-bank owner was being wooed by other large banks in the state and was holding out for a price close to three times book value. Moreover, he wanted stock, not cash.

Naturally, our fellows caved in and agreed to this value-destroying deal. “We need to show that we are in the hunt. Besides, it’s only a small deal,” they said, as if only major harm to shareholders would have been a legitimate reason for holding back. Charlie’s reaction at the time: “Are we supposed to applaud because the dog that fouls our lawn is a Chihuahua rather than a Saint Bernard?”

The seller of the smaller bank – no fool – then delivered one final demand in his negotiations. “After the merger,” he in effect said, perhaps using words that were phrased more diplomatically than these, “I’m going to be a large shareholder of your bank, and it will represent a huge portion of my net worth. You have to promise me, therefore, that you’ll never again do a deal this dumb.”

Yes, the merger went through. The owner of the small bank became richer, we became poorer, and the managers of the big bank – newly bigger – lived happily ever after

The Annual Meeting

The meeting this year will be held on Saturday, May 1st. As always, the doors will open at the Qwest Center at 7 a.m., and a new Berkshire movie will be shown at 8:30. At 9:30 we will go directly to the question-and-answer period, which (with a break for lunch at the Qwest’s stands) will last until 3:30. After a short recess, Charlie and I will convene the annual meeting at 3:45. If you decide to leave during the day’s question periods, please do so while Charlie is talking. (Act fast; he can be terse.)

The best reason to exit, of course, is to shop. We will help you do that by filling the 194,300-squarefoot hall that adjoins the meeting area with products from dozens of Berkshire subsidiaries. Last year, you did your part, and most locations racked up record sales. But you can do better. (A friendly warning: If I find sales are lagging, I get testy and lock the exits.)

GEICO will have a booth staffed by a number of its top counselors from around the country, all of them ready to supply you with auto insurance quotes. In most cases, GEICO will be able to give you a shareholder discount (usually 8%). This special offer is permitted by 44 of the 51 jurisdictions in which we operate. (One supplemental point: The discount is not additive if you qualify for another, such as that given certain groups.) Bring the details of your existing insurance and check out whether we can save you money. For at least 50% of you, I believe we can.

Be sure to visit the Bookworm. Among the more than 30 books and DVDs it will offer are two new books by my sons: Howard’s Fragile, a volume filled with photos and commentary about lives of struggle around the globe and Peter’s Life Is What You Make It. Completing the family trilogy will be the debut of my sister Doris’s biography, a story focusing on her remarkable philanthropic activities. Also available will be Poor Charlie’s Almanack, the story of my partner. This book is something of a publishing miracle – never advertised, yet year after year selling many thousands of copies from its Internet site. (Should you need to ship your book purchases, a nearby shipping service will be available.)

If you are a big spender – or, for that matter, merely a gawker – visit Elliott Aviation on the east side of the Omaha airport between noon and 5:00 p.m. on Saturday. There we will have a fleet of NetJets aircraft that will get your pulse racing.

An attachment to the proxy material that is enclosed with this report explains how you can obtain the credential you will need for admission to the meeting and other events. As for plane, hotel and car reservations, we have again signed up American Express (800-799-6634) to give you special help. Carol Pedersen, who handles these matters, does a terrific job for us each year, and I thank her for it. Hotel rooms can be hard to find, but work with Carol and you will get one.

At Nebraska Furniture Mart, located on a 77-acre site on 72nd Street between Dodge and Pacific, we will again be having “Berkshire Weekend” discount pricing. To obtain the Berkshire discount, you must make your purchases between Thursday, April 29th and Monday, May 3rd inclusive, and also present your meeting credential. The period’s special pricing will even apply to the products of several prestigious manufacturers that normally have ironclad rules against discounting but which, in the spirit of our shareholder weekend, have made an exception for you. We appreciate their cooperation. NFM is open from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. on Sunday. On Saturday this year, from 5:30 p.m. to 8 p.m., NFM is having a Berkyville BBQ to which you are all invited.

At Borsheims, we will again have two shareholder-only events. The first will be a cocktail reception from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. on Friday, April 30th. The second, the main gala, will be held on Sunday, May 2nd, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. On Saturday, we will be open until 6 p.m.

We will have huge crowds at Borsheims throughout the weekend. For your convenience, therefore, shareholder prices will be available from Monday, April 26th through Saturday, May 8th. During that period, please identify yourself as a shareholder by presenting your meeting credentials or a brokerage statement that shows you are a Berkshire holder. Enter with rhinestones; leave with diamonds. My daughter tells me that the more you buy, the more you save (kids say the darnedest things).

On Sunday, in the mall outside of Borsheims, a blindfolded Patrick Wolff, twice U.S. chess champion, will take on all comers – who will have their eyes wide open – in groups of six. Nearby, Norman Beck, a remarkable magician from Dallas, will bewilder onlookers. Our special treat for shareholders this year will be the return of my friend, Ariel Hsing, the country’s top-ranked junior table tennis player (and a good bet to win at the Olympics some day). Now 14, Ariel came to the annual meeting four years ago and demolished all comers, including me. (You can witness my humiliating defeat on YouTube; just type in Ariel Hsing Berkshire.)

Naturally, I’ve been plotting a comeback and will take her on outside of Borsheims at 1:00 p.m. on Sunday. It will be a three-point match, and after I soften her up, all shareholders are invited to try their luck at similar three-point contests. Winners will be given a box of See’s candy. We will have equipment available, but bring your own paddle if you think it will help. (It won’t.)

Gorat’s will again be open exclusively for Berkshire shareholders on Sunday, May 2nd, and will be serving from 1 p.m. until 10 p.m. Last year, though, it was overwhelmed by demand. With many more diners expected this year, I’ve asked my friend, Donna Sheehan, at Piccolo’s – another favorite restaurant of mine – to serve shareholders on Sunday as well. (Piccolo’s giant root beer float is mandatory for any fan of fine dining.) I plan to eat at both restaurants: All of the weekend action makes me really hungry, and I have favorite dishes at each spot. Remember: To make a reservation at Gorat’s, call 402-551-3733 on April 1st (but not before) and at Piccolo’s call 402-342-9038.

Regrettably, we will not be able to have a reception for international visitors this year. Our count grew to about 800 last year, and my simply signing one item per person took about 21/2 hours. Since we expect even more international visitors this year, Charlie and I decided we must drop this function. But be assured, we welcome every international visitor who comes.

Last year we changed our method of determining what questions would be asked at the meeting and received many dozens of letters applauding the new arrangement. We will therefore again have the same three financial journalists lead the question-and-answer period, asking Charlie and me questions that shareholders have submitted to them by e-mail.

The journalists and their e-mail addresses are: Carol Loomis, of Fortune, who may be e-mailed at cloomis@fortunemail.com; Becky Quick, of CNBC, at BerkshireQuestions@cnbc.com, and Andrew Ross Sorkin, of The New York Times, at arsorkin@nytimes.com. From the questions submitted, each journalist will choose the dozen or so he or she decides are the most interesting and important. The journalists have told me your question has the best chance of being selected if you keep it concise and include no more than two questions in any e-mail you send them. (In your e-mail, let the journalist know if you would like your name mentioned if your question is selected.)

Neither Charlie nor I will get so much as a clue about the questions to be asked. We know the journalists will pick some tough ones and that’s the way we like it.

We will again have a drawing at 8:15 on Saturday at each of 13 microphones for those shareholders wishing to ask questions themselves. At the meeting, I will alternate the questions asked by the journalists with those from the winning shareholders. We’ve added 30 minutes to the question time and will probably have time for about 30 questions from each group.

At 86 and 79, Charlie and I remain lucky beyond our dreams. We were born in America; had terrific parents who saw that we got good educations; have enjoyed wonderful families and great health; and came equipped with a “business” gene that allows us to prosper in a manner hugely disproportionate to that experienced by many people who contribute as much or more to our society’s well-being. Moreover, we have long had jobs that we love, in which we are helped in countless ways by talented and cheerful associates. Indeed, over the years, our work has become ever more fascinating; no wonder we tap-dance to work. If pushed, we would gladly pay substantial sums to have our jobs (but don’t tell the Comp Committee).

Nothing, however, is more fun for us than getting together with our shareholder-partners at Berkshire’s annual meeting. So join us on May 1st at the Qwest for our annual Woodstock for Capitalists. We’ll see you there.